Edward Wilmot Blyden's Contribution to Intellectual History: Transcending Gender, Race, and Ethnicity

By Dr. Murv L. Kandakai Gardiner

The Perspective

Atlanta, Georgia

September 15, 2017

|

|---|

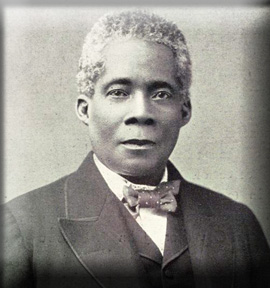

| Edward Wilmot Blyden |

As we seek to complement the efforts of our champions of education in Liberia by coming home to participate in the comprehensive nation's building that our president has envisaged and perennially encouraged, let us resist becoming intellectually lethargic and myopic by focusing on the major contribution to intellectual history by the nation's premier educator, Edward Wilmot Blyden. In this essay, as a psychologist, I shall be making the case that one of Blyden's major contributions to intellectual history was his quest to decolonize the African mind in order to mediate and resuscitate the African personality.

When we speak of personality what are we talking about? Are we defining it via the lenses of persona and montage which mean mask? Does one's DNA shape her/his personality and consequently his destiny? Or does our destiny shape our identity as Africans and ultimately our personality? It was only one man in intellectual history who provided the most critical insight into the problem of existential identity that many Africans endured towards the understanding of the African personality. That man was Edward Wilmot Blyden. Born in Charlotte Amalie, St Thomas (Danish) Virgin Islands which is now U.S. Virgin Islands in 1832, Blyden emigrated to Liberia in 1851. He suffered a painful humiliation at the divinity school of Rutgers College in New Brunswick, New Jersey as he was denied admission because he was black prior to his voyage to Liberia.

Blyden's ultimate purpose was clearly the vindication of Africa primarily through psychological liberation and systematic interaction with his sisters and brothers in Africa, Palestine, and Europe. Yet for him, as a Christian with a broader (Islamic) worldview, such vindication was not attainable apart from the Hebraic vindicator (go'el). For Blyden, there could be no true liberation of his African brothers in the midst of their systemic marginalization of their African sisters. Thus, gender equity was also primordial to the decolonization of the African mind. Toward this end, Blyden organized a special program for women at Liberia College when he served that institution as president. As he continued to make the case that gender parity was also part of the criteria for the decolonization of the African mind, he asserted accordingly,

I think that the progress of the country will be more rapid and permanent when the girls receive the same general training as the boys...We need not fear that our women will be less graceful, less natural, or less womanly; they will make wiser mothers, more appreciative wives, and more affectionate sisters. (1867, 103)

As Blyden understood it, what was grossly inadequate among most Europeans was their distorted view of African culture. Even as Hegel captivated the world including many African American and African scholars with his philosophy of history as a juxtaposition of divine providence with the evils of this world, he was latently racist. Hegel insisted that the Orientals did not know that men were free. And because they did not know, they themselves were not free. In his Lectures on Philosophy of World History, in the Hegel (rev.ed1975) asserted that only the Germanic nations due to the rise of European Christianity knew that the freedom of spirit is man's very essence. Hegel, then, paradoxically stated that civilization began in Asia and culminated in Europe. Either Hegel did not know that civilization began in Africa or he blatantly lied about it.

In light of the vicissitude of slavery, Blyden accentuated in his newspaper, A Voice from Bleeding Africa,

What under the sun, can be worse than slavery, that mystery of iniquity by which energies of men are crushed and their spirit of manliness and independence almost extinguished. What condition can be worse to a rational being than that which deprives him of the right to exercise those powers which God has given him in such a way as he of whom he stands equal in the eye of the great creator?

Blyden clearly became the embodiment of courage. And his aptitude for confidence indeed peaked as he resisted all forms of diffidence some elements of Western society tried to superimposed upon him. In the same publication, he also referenced major African scholars like J.E.J. Captain, A.W. Amo, Toussaint l'Overture, and Alexander Dumas. Thus, he asserted, "In view of such examples of intellectual and moral greatness as we have mentioned, shall ordinary white men as the majority of American slave-holders are, despise and insult the race from which they sprung, and allege its inferiority, in justification of their most horrible system?" Yet Blyden felt that Africans would be undermining their own progress if they promote race antagonism. For him, the solution lied in finding a depth culture, one in which the settlers could interact more intimately with their interior sisters and brothers. Insisted Blyden in his Christianity, Islam, and the Negro Race, "We must study our brethren of the interior, who know better than we do the laws of growth for the race" (90).

In a world where neuroses masqueraded as demons, some whites historically abnegated their African ancestry. And in so doing, they projected their inner weakness and sense of inferiority to black Africans. By the same token, some Africans with darker pigmentation in Africa, in succumbing to the neurosis, hated and systemically killed other Africans with lighter complexion. But Blyden, despite his rejection and humiliation by some members of the white race in America, transcended to a higher morality by embracing all of Europe and the rest of the world.

Blyden was very compelling in his argument that the slavery of the mind is far more destructive than the slavery of the body. He went on to reiterate in the aforementioned publication what he previously accentuated in his Inaugural Address at Liberia College that "if slavery finds residence in the mind, it becomes far more subversive than the ancient physical fetters." Therefore, for Blyden, the issue became, what lies in the colonized mind? For him, it was the rigors mortis of inferiority.

In the relatively new Republic affected in some way by the American Civil War and Reconstruction, Blyden in his Inaugural Address at Liberia College (UL) in 1881 mediated existential hope as he averred:

It is our hope and expectation that there will rise up men and women aided by institution and culture,...imbued with public spirit, who will know how to live and work and prosper....how to use all favoring outward conditions, how to triumph by intelligence, by tact, by industry, by perseverance, over the indifference of their own people, and how to overcome the scorn and opposition of the enemies of the race.

For Blyden, the telos of education is not simply the provision of information, but rather the formation of the mind. Clearly, for him, as he articulated in his 1881 Inaugural Address, if the formation of the mind is secured, the information will take care of itself. Mere information of itself is not power, but the ability to know how to use that information-- and this ability belongs to the mind that is disciplined, trained, and ultimately decolonized. Says Blyden, you can have ample storage of information in the mind. But if the mind is not trained to appropriate them, they will just lie there like useless lumbers.

Blyden envisaged the ideal educational curriculum that would accentuate sensitivity to the value of native African culture. This was the only tool that he believed could defeat colonialism and embrace modernity that could be synthesized with native cultural resources. In this light, Blyden would be proud of the efforts of some young Africans who are making some technological breakthroughs with search engines that are tantamount to Google. He would also be proud of many African women and men in their creative fusion of African clothing and hair braiding and weaving, unique improvisation and syncopation in Ethiopian, South African, and African American Jazz and Gospel music coupled with enhanced innovation in other modes of African visual and performing arts which are helping to transform many Africans and non-Africans globally.

Blyden also strongly felt that the core of Africa's educational curriculum should be based upon traditional concepts of education. In Christianity, Islam, and the Negro Race, Blyden (1888) makes the point that the African curriculum must provide a strong explication about Africans in harmony with God, nature, and the universe. There is no alienation. Unlike the European worldview which posits that collective man is constantly crashing with God and nature with alarming indifference to the universe, the African worldview contends that the basic modes of human action are cooperation, peace, and developing great architectures. Even Blyden would acknowledge here that the Black race along with other races have historically been in rebellion with God and have participated greatly in the ecological destruction of this sacred earth. But with the ideal educational curriculum in place, both economic development and harmony with the ecosphere are attainable.

In light of the atrocity of the middle passage and the entre Trans-Atlantic slavery as well as the carnage experienced by the slaves from the James River to the Mississippi River, the negro cries out in the personage of Langston Hughes:

I've known rivers

Ancient dusky rivers

I've known the rivers of

the Nile and Congo!

My soul bursts like the river.

And Arthur Symon:

O river! water of my soul

Is it I? Is it I? All night long...

the river is crying out to me.

In his Lecture to the Young Men's Literary Association of Sierra Leone, Blyden (1893) articulated, "It is sad to think that there are some Africans who are saying , 'Let us do away with our African personality and be lost, if possible, in another race.' But to retain race integrity and race individuality is no easy task in the hard, dogmatic and insurgent civilization in which we live."

As the pilgrim pioneer to liberate and decolonize the African mind, Blyden anticipated major trailblazers and torch bearers of African redemption like Kwame Nkrumah, Sekou Toure, Julius Nyrere, Jomo Kenyatta, Nnamdi Azikwe, Oliver Tambo, Nelson Mandela, Joshua Nkwomo, Ami Jacques Garvey, George Padmore, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and Nkosazana Zuma.

However, it was the African psychiatrist, Frantz Fanon who best collapsed Blyden's intellectual stream into his writings. Blyden (1888) contended, "It has been said that the fringe of European civilization is violence. Even aid agencies, philanthropic, political and commercial are all tending to fashion us after the pattern which Europe holds out. But if you surrender your personality you have nothing left to give to the world." Building upon Blyden's foundation, in his conclusion of The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon asserted, "We can modernize without engaging in the game of catching up to Europe, for ultimately, it will be sickening to many Europeans if all we can do is to present a replica of Europe... For Europe, for ourselves, and for humanity, we must turn over a new leaf. We must build new concepts and create a new humanity."

For Blyden and later Pan-Africanists, Africans were destined to make their greatest contribution to the world spiritually and culturally. Their spirituality and culture shaped their identity and African personality. Thus, the African personality was marked by cheerfulness, love of nature and willingness to serve.

We can see the imprints of Blyden's writings, his contribution to intellectual history in the works of Leopard Senghor, Antonio Gramsei, and Fanon aforementioned. Even the great Swiss psychoanalyst, Carl Jung may have inappropriately borrowed Blyden's concept of the Collective Self. Jung' theory of the Collective Unconscious was taken from Blyden without giving him the credit. And Jung took a step further in distorting the African personality. Jung emerged on the scene several years after Blyden. And he and his editor, Joseph Campbell wrote as if Jung traveled into every African village to understand the Collective Unconscious, especially the evil side of it. Thus, Jung and Campbell set the stage in relegating the African personality as evil and demonic.

Like the prophets Jeremiah and Jonah who plunged deeply into the Hebraic subconscious/unconscious in order to excavate the truth, Blyden entered into the depths of the African subconscious/unconscious by embarking on a voyage of self-discovery/a creative pilgrimage in Africa and ultimately Palestine. First, he wanted the ruling elites of Liberia to listen to the cries of their ancestors and enter the depths of their existence by going into the interior of Liberia in order to excavate the truth and strength of the nation. Accordingly, he called on the settler class to lend their ears to the music, working skills, and other dexterities of the indigenous class.

Second, in his trajectory of going into the depths of the African unconscious, while on a steam liner,Blyden experienced the beauty and ecological harmony in the place where he called the most beautiful site in all of Liberia, Cape Mount, land of my fathers. Blyden was right. But Cape Palmas, land of my mothers, is the most beautiful place in Liberia. He described how the banana, plantain, orange, and plum trees affected him, how the lofty and venerable trees gave him a feeling that reminded him of Funchal, Madeira. In the land of my fathers, Blyden was filled with exuberance comparable to his first glimpse of the first light house in the world in Alexandria, Egypt.

Third, the most pivotal and turning point in Blyden's pilgrimage which made the critical difference in his contribution to intellectual history was when he found himself before the Pyramids which were built by ancient Africans/blacks centuries before Jewish servitude via the tyrannical rapacity of Pharaoh. On behalf of the wretched of the earth, on behalf of a people whose history was distorted by others who even used the scripture to lie about them in a successful attempt to relegate them into inferiority, and on behalf of Europe also, Blyden did the needed exegesis of Genesis 9 - 11 to accentuate the truth that ancient Africans/Cushites/blacks built the tower of Babel. In his work From West Africa to Palestine Blyden (1873) reiterates the words in the Masoretic text that during the scattering, the children of Ham who had previously built the tower of Babel found their way into Egypt and also built the Pyramids.

Thus, finding himself before the Pyramids, while standing in the central hall of one of the seven wonders of the ancient worlds, Blyden meditated on the words of Hilary Teague. Those words should be transmitted to everybody and every other branch of humanity who are striving technologically, economically, spiritually, and ecologically for a better day in Liberia. And so today, we join Teague and Blyden from the depths of the African unconscious with urgency in saying:

From Pyramidal hall,

From Karnac's sculptured wall,

From Thebes they loudly call--

Retake your fame.

For Teague and Blyden, in building the tower of Babel and the Pyramids, our African ancestors had fame. And it behooves us to strive by greater works and ingenuity to "retake it." Blyden felt because he was a progeny of Nimrod,, Ham, Noah, and those other illustrious Africans, "blood seemed to flow faster through his veins." Says Blyden, "I seemed to feel the impulse from those stirring characters who sent civilization into Greece...I seemed to catch the sound of the 'stately steppings' of Jupiter, as he perambulates the land on a visit to my ancestors, 'the blameless Ethiopians' (105).

In his The Shaking of the Foundations Tillich reminds us:

We are estranged from the Ground of our being, because we are estranged from the origin and aim of our life. And we do not know where we are going. We are separated from the mystery, the depth, and the greatness of our existence. We hear that voice from the depth, but our ears are closed. We feel that something radical, total, and unconditioned is demanded of us; but we rebel against it, try to escape its urgency, and will not accept its promise.

As indicated earlier, Blyden descended into the African unconscious via the psychological, physical, and spiritual depths of Liberia, Sierra Leone, Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt in order to excavate the truth. Indeed in so doing, he also went down into the valley of potteries where he saw the despair and dislocation of his people caused by the perpetuation of false otherness. Yet he did not give up hope because he saw the potter molding, remaking, and reshaping the clay in his hand. He also made a creative pilgrimage to Lebanon and Israel.

Europe's expansion of colonialism in Africa precipitated a major ethnic and cultural disintegration. Nevertheless, Blyden held that amidst the lingering problem of omnipotence among many Africans, which resulted in divide and conquer, thus signifying the destruction of African civilization, there existed a common collective consciousness of belonging together. Therefore, like Cinque of the Mende tribe, who was taken along with several of his country men and women from Sierra Leone on the notorious Portuguese vessel, the Tecora to the Americas, Blyden invoked the help of his ancestors, and of history itself in that inner spiritual striving for the redemption of Africa in believing that the moment of testing, the hour of tribulation and its resultant liberation was the reason for which he was born.

Blyden went on to say that Africa may yet prove to be the spiritual conservatory of the world. Even George W. Bush though speaking only from a geo-political interest in Abuja, alluded that Africa is the continent of the future. President Bush said, "Africa is a continent of possibilities"(Bush 2003). His statement reflects the Western world's geo-political posture that is predicated on Africa's mineral resources like coltan, the life-line for cell phones which can only be found in the DRC, uranium, diamond, gold, iron ore, other natural resources like rubber, coffee, cocoa, and sugar cane in Liberia and other parts of Africa.

Blyden (1888) averred in his Christianity, Islam, and the Negro Race, that when the Western nations diminish their spirituality due to their preoccupation with materialism, they will one day turn to Africa for help in order to be redeemed. And in amalgamating Psalm 68:31 with the kenosis passage in Philippians 2, he asserted, The promise of Africa is that she shall stretch forth her hands unto God. Ethiopia having always served, will continue to serve the world. African slaves, "the stream of humanity has cultivated half the western continent. It has created commerce and influenced its progress." In the words of Mrs. Nkosazana Zuma of the African Union, "There is no America without Africa."

Blyden finally compared Africa with Deutero Isaiah's suffering servant and the Christ figure in Philippians. The lot of Africa, says Blyden, resembles also the one who made himself of no reputation, but took upon himself the form of a servant. He went through kenosis, that is, he went through the process of emptying himself to be perfect through suffering.

Yet Blyden was highly critical of many Christian missionaries for committing what he called the "sin of cultural alienation." That sin, entailed the missionaries' attempt to Europeanize Africans, which was hindering the development of the African personality (1888, 65-72). He instead, preferred a Christianity suitable to the African context. He argued that Islam, on the other hand, had accorded Africans the privileges of a major world civilization without creating in them a sense of inferiority. Thus, very assiduously, he repudiated the sense of inferiority projected by many missionaries and other members of the American Colonization Society (ACS) in calling Africans heathens and pagans. In this light, Blyden would strongly condemn the recent racial violence in Charlottesville, Virginia. He would also condemn all forms of ethnic hatred that are pervasive in Liberia and other parts of Africa. He believed every word in Cowper's lines:

Fleecy looks and dark complexion

Cannot forfeit nature's claim;

Skin may differ, but affection

Dwells in white and black the same.

The legacy of Edward Wilmot Blyden challenges us to reclaim our true nature and culture, thus reclaiming our true cultural and spiritual personality, to keep the faith, to cognitively refute and obliterate the negative thoughts and attitudes directed upon all of us as Africans and upon our progeny, so at last we can enhance a collective self-esteem and regain a literate African culture.

References

Blyden, Edward Wilmot. (1856). Voice from a Bleeding Africa. Monrovia: Liberia

____________________.(1869). The Negro in Ancient History. London: McGill & Witherow

____________________.(1873). From West Africa to Palestine. London: WB. Wittingham. Reprinted 2013. New York: The Classics.us

____________________.(1994). Christianity, Islam, and the Negro Race, Baltimore: Black Classic Press

____________________. (1893). Lecture to the Young Men's Literary Association of Sierra Leone. Freetown: Sierra Leone.

Bush, George W. (2003). Speech on Africa. Abuja: Nigeria

Hegel, Georg Freiderich. (1914). Lectures on Philosophy of World History. London: Bell

Hughes, Langston. (1970). The Negro Speaks of River. New York: Printed in The Crisis 60th Anniversary

Tillich, Paul. (1948). The Shaking of the Foundations. New York: C. Scribner's Sons

Zuma, Nkosazana (2015). Welcome Remarks as Chairman of the African Union on the Occasion of President Obama's Visit. Addis Ababa:

Ethiopia.

Amesegenalehu/Thank you

The author: Dr. Murv L. Kandakai Gardiner is Professor of Psychology and Chairperson of the Diversity Lecture Series at the William V.S. Tubman University

Harper, Maryland County, Liberia.He can be reached for comments at mgardiner@tubmanu.edu.lr and at murvgardiner@gmail.com